In Malaysia, business and human rights must go hand in hand, UN rights chief says

Malaysia has been in the spotlight for months over allegations that forced labour, debt bondage and scam jobs – in particular targeting Bangladeshi migrants – have riddled its recruitment market for foreign labour.

Anwar’s government has been working hard to attract foreign investment into the country to boost Malaysia’s sluggish economy.

There is a need to establish a human rights-based migration plan to tackle exploitation, extortion and ill-treatment of low-wage migrant workers, including foreign domestic employees, Turk said, saying Malaysia is not alone when it comes to these issues.

A panel of UN labour analysts in April said large amounts of money were being made in a labour racket run by “criminal networks” between Malaysia and Bangladesh.

“We received reports that certain high-level officials in both governments are involved in this business or condoning it,” the analysts, including agency officials on anti-trafficking and modern day slavery – said in a statement. “This is unacceptable and needs to end.”

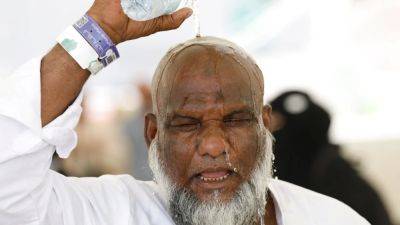

Malaysia on Friday closed its borders to new migrant workers, sparking chaos at Dhaka’s Shahjalal International Airport and Kuala Lumpur International Airport, as thousands of Bangladeshi migrant workers scrambled to catch last-minute flights before the midnight deadline.

Hopeful “remittance warriors” – as Bangladesh’s overseas workers are known – paid as much as US$1,000 for a seat on the last flights to Kuala Lumpur, to avoid being stranded at home after having paid thousands of dollars more to recruitment agents to secure visas.

Bangladesh’s labour bureau reported that some 17,000 people missed that midnight deadline.

Desperate to jumpstart its post-pandemic recovery, Malaysia has provided few safeguards to the